Kelp Forests, Urchins and Sea Stars: A Delicate Balance

The kelp forests off the coast of California are some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet. Known as the “sequoias of the sea”, some species of kelp can reach heights of 150 feet and grow up to 2 feet per day, absorbing vast amounts of carbon dioxide. Kelp forests provide food and shelter for hundreds of marine species, from tiny amphipods to playful sea lions and even migrating gray whales. They also act as a nursery for juvenile sharks by offering protection from predators as well as an abundance of prey, like stingrays.

When protected, kelp creates a marine habitat that is rich in fish and other sea life, which can provide an abundance of food for coastal communities. These underwater forests also prevent erosion by reducing the speed and size of waves and protect the coast from storm-driven tides and surges. Although kelp forests are crucial for the health of our planet, we’re losing these habitats at an alarming rate. Kelp in some areas of Southern California has been reduced by 75 percent, and Northern California has seen their kelp canopy drop by 95 percent in recent years. Pollution, climate change, and overfishing have taken a toll on kelp around the globe.

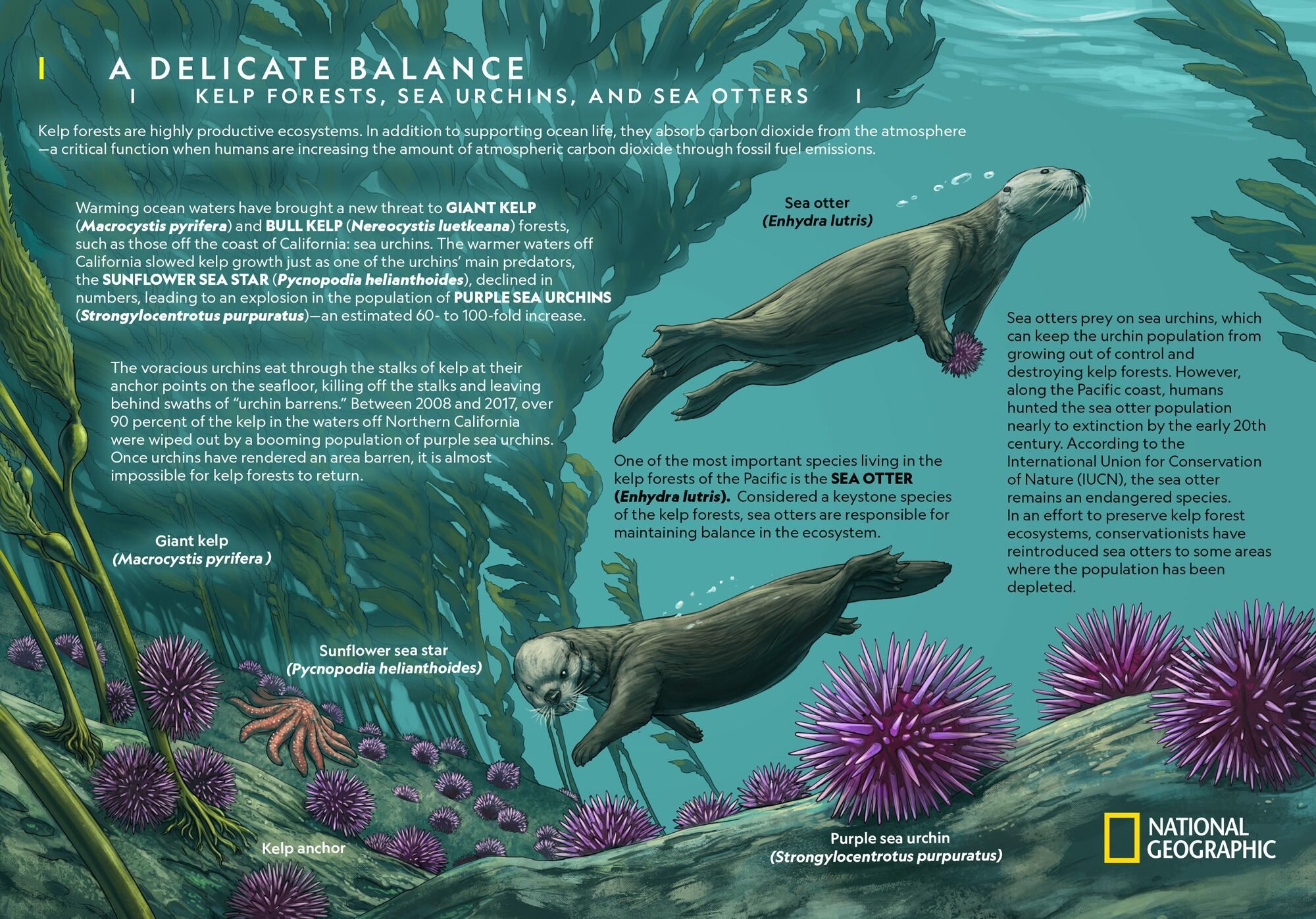

Like any ecosystem, the species within a kelp forest habitat all work in harmony together, and one imbalance can throw everything off. This is known as a trophic cascade - when a keystone species is reduced or removed from the food web, it affects the entire ecosystem. This is what happened to the kelp forests of California.

Purple sea urchins are a natural part of kelp ecosystems, but when predators that keep their numbers in check started to disappear, the urchin population boomed. In herds, urchins can consume kelp at a rate of 30 feet per month, creating urchin barrens. They can survive long after their food source is depleted, giving them the nickname of “zombie urchins”. Kelp forests depend on predators, like otters and sheepshead, to keep the purple urchin populations in balance. One of these predators, the sunflower sea star, has been important in keeping urchins at bay along the Pacific coast. However, warming oceans -- and one marine heatwave event in particular -- exacerbated a disease that decimated sea star populations. In just three years, sea star wasting syndrome killed off more than 90% of the global population.

The demise of California’s kelp forests is a perfect example of how small impacts to an ecosystem can have drastic consequences. The establishment of marine protected areas is an important step in protecting these critical habitats from further degradation and giving them an opportunity to grow back.

More info on the topic

An excellent video about the urchin issue on CNN.com: Saving California's kelp forests from 'zombie' urchins.

They also produced a great video: https://www.cnn.com/videos/tv/2021/07/26/cte-saving-californias-kelp-forests-video.cnn.